'Lieutenant colonel Yusuf al-Jadir made a strategic advance in one of the suburbs of Aleppo on December 15, 2012, destroying several tanks of Syrian regime leader Bashar al Assad.

One of his fighters asked him how he was feeling about the victory. Jadir said, “By God, I’m really sad. These tanks are our tanks, the ammunition [of the enemy] is ours, and the people we are fighting are our brothers. By God, I feel sad whenever one of us or them get killed. If that man [Assad] had resigned, Syria would have been one of the best countries in the world.”

Born in 1970 in the suburbs of eastern Aleppo, Jadir defected from Assad’s military in July 2012. Five months later, a few hours after gaining hold of an Aleppo suburb, he was killed in an air raid.

Jadir was among the most influential military officers who defected from the regime’s army in the summer of 2012. Though the “Free Syrian Army” was officially launched in July 2011, more and more soldiers joined the revolutionary ranks by 2012, a defining moment for tens of thousands of Syrians who protested against the Assad regime.

But seven years later, the Free Syrian Army (FSA) is no longer a well organised conglomerate of several fighting units. It is rather a deeply fragmented resistance movement that is spread across Syria, holding up key territories in Daraa, Idlib provinces, Aleppo suburbs and Ghouta, a Damascus suburb.

What happened between 2011 and 2017 is a story of Assad’s brutal military campaign aided by Russia and the culmination of several dozen fighting units backed by international players that changed the course of Syria’s revolution, pushing the country to a full-fledged civil war.

From 2012 onward, competing ideologies and interests caused cracks in the opposition. Some battalions and brigades started to form their own agendas beside toppling Assad.

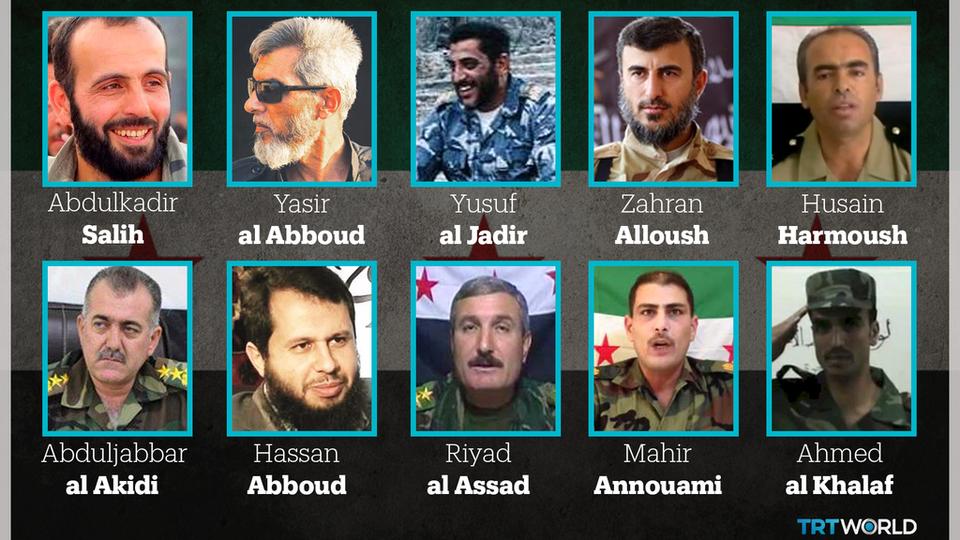

To understand why the revolutionary forces were able to make strategic gains in the initial years, one must look into the lives of some of its key leaders. They were somehow able to bridge a gap between various fighting forces – whether they were “moderate”, “Islamists” or “patriotic.” And even today, the space they left seems to be unfilled. And until now, they are proving to be the irreplaceable leaders of the revolution.

Yusuf al Jadir defected from Assad’s army on July 18, 2012, and took the leadership role of Al Tawheed Brigade, one of the biggest armed oppositions in Aleppo. In its heyday, the brigade had at least 10,000 fighters.

Jadir participated in many battles against the regime forces north of Aleppo. He died in an air raid on December 15, 2012. Instead of harbouring the feelings of enmity, anger or revenge, Jadir looked after the welfare of hostages or the regime soldiers who surrendered in various battles. Many Syrians consider him as a national figure.

Jadir participated in many battles against the regime forces north of Aleppo. He died in an air raid on December 15, 2012. Instead of harbouring the feelings of enmity, anger or revenge, Jadir looked after the welfare of hostages or the regime soldiers who surrendered in various battles. Many Syrians consider him as a national figure.

Zahran Alloush wa born in 1971 in eastern Ghouta, Alloush came from a family of religious scholars. He studied in Saudi Arabia, where he finished his MA in Islamic Studies at the Islamic University.

He was known for being “moderate active Salafi,” a title that landed him in trouble. The regime arrested him for holding Salafist views in 2009.

Soon after the armed rebellion gained momentum, Assad released thousands of prisoners. Alloush was also set free. He was quick to gather fighters and form what he called the Islam Platoon, which gained several territories. He then named it the Army of Islam with more than 10,000 fighters under his belt.

Under Alloush’s military command, Daesh failed to impose its presence in eastern Ghouta. Alloush was against the extremist group, often referring to it as the “Baghdadi Gang”.

A few months before his death, foreign countries intervened against the revolutionary fighters, giving an advantage to the Assad regime, Alloush launched a key battle in Ghouta that enabled the opposition forces to get closest ever to Assad’s stronghold, Damascus.

But he was killed by a Russian air strike on December 25, 2015.

Known by his nickname “Hajji Mare,” Abdulkadir Salih was born in 1979 in Aleppo. Prior to the revolution, he used to be a grain merchant. As protests against Assad morphed into a nationwide uprising, Salih organised many demonstrations.

He was known for being “moderate active Salafi,” a title that landed him in trouble. The regime arrested him for holding Salafist views in 2009.

Soon after the armed rebellion gained momentum, Assad released thousands of prisoners. Alloush was also set free. He was quick to gather fighters and form what he called the Islam Platoon, which gained several territories. He then named it the Army of Islam with more than 10,000 fighters under his belt.

Under Alloush’s military command, Daesh failed to impose its presence in eastern Ghouta. Alloush was against the extremist group, often referring to it as the “Baghdadi Gang”.

A few months before his death, foreign countries intervened against the revolutionary fighters, giving an advantage to the Assad regime, Alloush launched a key battle in Ghouta that enabled the opposition forces to get closest ever to Assad’s stronghold, Damascus.

But he was killed by a Russian air strike on December 25, 2015.

Known by his nickname “Hajji Mare,” Abdulkadir Salih was born in 1979 in Aleppo. Prior to the revolution, he used to be a grain merchant. As protests against Assad morphed into a nationwide uprising, Salih organised many demonstrations.

Salih felt the urge to protect the people of Aleppo as the regime deployed brutal tactics to quell the uprising, often killing unarmed protesters, torturing and disappearing people. He joined the armed opposition and became one of the founding members of Al Tawheed Brigade, which succeeded in taking control of more than half of Aleppo.

Salih organised many rebel brigades in the region and was part of the FSA’s command structure.

He played a crucial role in bridging the gap between various opposition groups with different ideologies and schisms. His moderation was accepted by most of the fighting units in Aleppo and that alone led the regime to put a $200,000 bounty on his head, local experts say.

Salih survived at least two assassination attempts before he died on November 17, 2013, as a result of an air raid on the Infantry Academy of Al Muslimiyah north of Aleppo.

When some opposition fighters asked him about composing an anthem on his name, he said:

“If you want to write a song, do not mention my name, you could mention the name the Al Tawheed Brigade, the whole Muslim Nation, Syria, that is okay, however, don’t mention the name of a person. He might get arrogant."

So what changed after the revolution lost key leaders?

Aleppo’s largest Al Tawheed brigade collapsed soon after the death of Salih.

Rebel group Jaish ul Islam remained stuck in eastern Ghouta and never made any further advances after losing Zahran Alloush.

So far, no one has managed to replace them. Their charisma and ability to unite battalions and move away from the control of their funders made them indispensable.

Ahmad Abazzed, a military analyst from Daraa, said that the Assad regime had pinpointed these leaders and was desperate to eliminate them.

“Assad knew all the revolutionary forces were following the command of these charismatic leaders as they were from the first generation of rebels who fought against the regime,” Abazzed said.

It was clear, he added, that Assad’s and Russia’s first target was never Daesh or other extremist groups that killed in the name of religion, rather it was the FSA and other moderate opposition groups.

Though the strategy of bumping off top leaders worked with Al Tawheed and Jaish ul Islam, Abazzed said other battalions have learned to survive even after losing their main leaders.

“Because they have built an institutionalised structure and popular base among the masses.”

Moving forward, he said, the armed opposition has moved from building large military brigades to forming small and compact fighting units. “The new battalions that have been formed recently are easier to control than brigades that led the assault at the beginning of the revolution,” he said.

“I think regaining independence, strategic thinking, cultivating an understanding with various allies is important so that the opposition forces would be able to balance between the interests of the allies and the interests of the Syrian people.”

Abazzed said one thing was clear in the series of negotiations between the Assad regime and the opposition that took place in Geneva, Astana and Sochi. "The opposition should be able to represent Syria as a whole rather than representing local battalions or councils," he said. "Then only they can redefine themselves and stick to their main goal to topple Assad first.” '

Aleppo’s largest Al Tawheed brigade collapsed soon after the death of Salih.

Rebel group Jaish ul Islam remained stuck in eastern Ghouta and never made any further advances after losing Zahran Alloush.

So far, no one has managed to replace them. Their charisma and ability to unite battalions and move away from the control of their funders made them indispensable.

Ahmad Abazzed, a military analyst from Daraa, said that the Assad regime had pinpointed these leaders and was desperate to eliminate them.

“Assad knew all the revolutionary forces were following the command of these charismatic leaders as they were from the first generation of rebels who fought against the regime,” Abazzed said.

It was clear, he added, that Assad’s and Russia’s first target was never Daesh or other extremist groups that killed in the name of religion, rather it was the FSA and other moderate opposition groups.

Though the strategy of bumping off top leaders worked with Al Tawheed and Jaish ul Islam, Abazzed said other battalions have learned to survive even after losing their main leaders.

“Because they have built an institutionalised structure and popular base among the masses.”

Moving forward, he said, the armed opposition has moved from building large military brigades to forming small and compact fighting units. “The new battalions that have been formed recently are easier to control than brigades that led the assault at the beginning of the revolution,” he said.

“I think regaining independence, strategic thinking, cultivating an understanding with various allies is important so that the opposition forces would be able to balance between the interests of the allies and the interests of the Syrian people.”

Abazzed said one thing was clear in the series of negotiations between the Assad regime and the opposition that took place in Geneva, Astana and Sochi. "The opposition should be able to represent Syria as a whole rather than representing local battalions or councils," he said. "Then only they can redefine themselves and stick to their main goal to topple Assad first.” '

0 Response to "The Bravehearts of Syria"

Post a Comment